"What Keeps Me Fighting": Living with ALS

Eryn and Chad Blythe celebrate their completion of the 2017 L.A. Marathon for the ALS Association. (Photo by Loud Owl)

By Greg Lehman

The Finish Line

The wheels on Eryn Blythe’s wheelchair barely move when her husband Chad lifts her up and out of its seat. They have stopped just short of the Los Angeles Marathon finish line on March 19, 2017, some six hours after beginning the race at Dodger Stadium. Blythe’s frame is slight, but enough strength remains in her arms and legs to stand where Chad holds her wrists in his hands. After living with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, for three years, Blythe’s feet can still make a pigeon-toed contact with the ground. She slides one foot forward, then the other, as the pair closes the last bit of space between them and the end of the 26.2 mile journey.

The day marks the 18th year that the ALS Association's Orange County Chapter has sponsored a team of runners to push an ALS patient through the race. After tagging in teams of volunteers to help at every mile of the course, Blythe’s team stands aside at the finish to watch as the couple approaches the finish line alone.

Eryn Blythe nears the finish line with the support of her husband, Chad. (Photo by Loud Owl)

They step over together, where Blythe holds her husband for a moment on the other side. Not a dry eye can be found.

“There were times during the race that it almost felt like I was running again,” Blythe said later. “My legs hopped involuntarily the entire time, almost like they knew they were supposed to do something! It was a truly great experience.”

Every case of ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, forms its own unique journey for the patient and the people around them. Myriad unknowns surround this disease, from a concrete cause, to an effective treatment or cure for the cruelty it inflicts. These and other variables bring no shortage of bewilderment and frustration to everyone touched by ALS. There is no exaggeration in saying that the disease has and continues to fire on the limits of the psyche and science alike.

The Southern California area has generated more than a few responses to the traumas that come with this condition. Cooperation, hope, and resilience have yielded bounties in this region, testifying to the remarkable efforts of scientists, researchers, and the people who live with and around this disease every day.

As Stephen Winthrop, a trustee on the national board of the ALS Association who has been living with the disease since 2013, would say later, the world of ALS is “not just one story. It’s a constellation of stories that are waiting to be told.”

No Day is the Same

Since its first clinical description in the early 1800s, a definitive cause for ALS still remains elusive.

What is known is that the language of neural impulses shared between the brain and the body’s muscles, for some unknown reason, is lost. This essential communication that keeps most people operating normally are broken, stolen by something with a name but no explanation. The brain’s well-worn paths to tasks that become second nature to a person, known as motor plans, become forgotten to the body of those afflicted with this disease. This deterioration carries the name of ALS, but could be between 12 and 15 different diseases, in the same way that cancer covers many different varieties of rampant cellular growth. It might be a combination of unlikely variables meeting in one singular nightmare. A vicious mix of environmental elements, rare genetic defects, and a traumatic event like a concussion at a young age could unleash the disease, or diseases, on a person at any time in their life. Or it could be something else entirely.

The diaphragm, bulbar region, trunk, and appendages are the most common regions to show symptoms first, but the disease can show itself in other areas as well. There are exceptions to these effected areas, however. Sexual organs remain unscathed throughout the patient’s life, since involuntary muscles provide the bulk of sensation and responses associated with sex. Similarly, the brain remains intact from beginning to end as well, deepening the malevolent nature of the disease as one literally becomes trapped in their own body.

The broad range of time that patients survive, and when they are diagnosed, only deepen these and other mysteries as well. Even hard data about life expectancy and the rate of the disease’s progression collected so far is skewed by the fact that neurologists diagnose on a timescale ranging from a single visit to never. This leads to a divergence in even the number of cases in the United States, ranging from 15,000 to 35,000, with no one knowing for sure.

In spite of so many secrets that ALS has yet to reveal, what is clear to patients and everyone around them, from family members to physicians, are the drastic changes that come with the disease.

Blythe’s own diagnosis came at a uniquely significant time in her life. One month before she was due to give birth to her second child, a daughter, she received the news that she had ALS.

“To say the least, we were devastated,” Blythe said about her and her family. As with many other people living with this disease, a profound perspective arrived with her diagnosis. She was at turns steeped in resentment and acceptance, as well as everything in between, along the emotional spectrum of a terminal diagnosis.

“With this disease, no day is the same,” said Blythe. “I could tell you that today is a great day filled with lots of energy and excitement for the day,” Blythe said. “Then, two hours later, I can feel like a car with four flat tires and a dead battery.”

As her energy became more and more sapped by the progression of the disease, Blythe described her increase of reliance on others as a slow whittling away of her abilities.

“At first it was a little harder to do things such as getting in the car, or brushing my hair,” she said. “Then it slowly changed to asking for help once in a while, and gradually once in a while became a daily request. This is how all of the daily activities have gone.”

While ALS does interrupt the role of nerve cells, paralysis is not the culprit for the loss of movement in patients. Instead, muscles suffer from spasticity, in which they contract and become too tight to operate normally. Pain plays no small part in this proces. In a radio interview with KSBR in Orange County, Blythe described the cramping of tendons as a pulling effect so intense as to affect a burning sensation. Weakness takes over afterwards, even as the mind’s abilities remain. A patient’s mental faculties are untouched to the end, pinning them between the hardening walls that their bodies become.

“There is now a ‘dance’ every time I need to get dressed or perform a daily task that I have done for myself thousands of times before,” said Blythe. “My mind still knows how to do all of these things, but my body is too tight with spasticity, and my muscles too weak to force them to perform properly. Now it's almost impossible for me to stand by the sink on my own and balance just to wash my hands.”

The emotional toll of this dependance is significant for Blythe. “I can't tell you how hard it is to lose not only your independence, but to lose your self-confidence and dignity as well,” Blythe said. “Feeling humiliated because you now need a bib, like your babies, in order to eat. Because if you don't, there are stains and crumbs all over you, and that humiliates you more.”

Even so, Blythe’s thankfulness is clear and striking amidst trials that follow her at all times. “I feel pretty good at the moment,” she said, “and very grateful to be here.”

Stephen Winthrop, a trustee on the National Board for the ALS Association, knows the adversity that come with this disease intimately. When muscle twitches began in his left arm at the beginning of the decade, Winthrop said that, “like most guys, I just ignored the twitching for a while. It wasn’t until November 2013 that I was actually diagnosed with ALS.”

The final word on whether a person has ALS does not come by way of tests. Well-trained eyes, cross-referencing a host of different indicators, have to rule out everything else first. Possible, probable, and definite ALS are medical terms used to shrink the crosshairs of the potential to the concrete. Symptoms in one area fall in the parameters of the possible, two becomes probable, and three marks the undeniably definite. The only other way to a positive diagnosis is when upper motor neurons located in the brain and lower motor neurons in the spine show signs of weakening at the same time. In either case, this progressive weakening of muscles is then officially named for the patient, opening a veritable hive of bewildering possibilities and unanswerable questions.

Before this happened for him, Winthrop did “what nobody should, which is Googling their symptoms” after finding that his left arm was weaker than his right. This was strange to him, since he is left-handed.

Then, one night in late August of 2013, Winthrop came across a description of ALS.

“I had this, ‘Oh my god, is this possible?-moment,’” he said. A little over two months later he was officially diagnosed.

For Winthrop, telling his children, 12 and 15 years old at the time, “was still easily the most horrific day of my life.”

At their age, his children were fully capable of questions “that could cut right to the heart of the matter. But my answers, it was a lot of ‘I don’t know’ or ‘There’s no way of knowing.’ Like, ‘Are you going to be there for my high school graduation, or college graduation?’ That was just a great big ‘I don’t know,’ because nobody knew.”

As with the majority of ALS patients, Winthrop’s case is sporadic, as opposed to familial. This means his case is without a genetic history of ALS or an environmental cause to pin partial responsibility.

Traceable or not, Winthrop felt as if his diagnosis untethered him and his family from the world they had known before. He described an onslaught of emotions rushing through his home like “a fog of shock and anguish and anger and numbness.”

After some time had passed, however, Winthrop found that his disease was not progressing as fast as it does in others. This realization found fertile ground in his decision to take every moment he could on his feet.

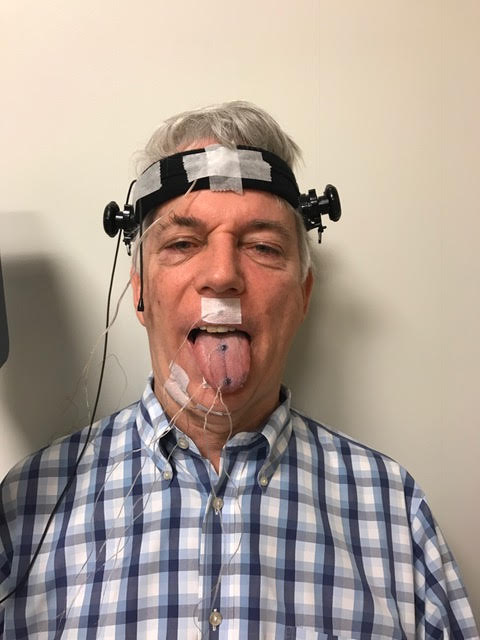

Stephen Winthrop, showing off his electrodes during a clinical trial. (Photo courtesy of Stephen Winthrop)

For the past year and a half, Winthrop has participated in clinical trials in which doctors have used electrodes to tally activity across his face and tongue as he reads and makes sounds. The signals that return from electrical stimuli to these regions are recorded, the results measured.

The study began before Winthrop showed any signs in his bulbar muscles, which are responsible for movements in the mouth and throat. Since one area of the body will usually show signs of ALS and spread from there, positioning tests to anticipate symptoms before the patient can feel them is a way for scientists to learn how the disease progresses over time.

Winthrop said that bulbar symptoms began to show in his body recently, an unexpected leap from his arms. Even with this new development, Winthrop does not hold back from sharing what he sees as an important break in his particular journey.

“I’m an outlier, and a very lucky outlier, within this very unlucky club of people who have ALS in two very important respects,” he said. First, Winthrop’s case is progressing at a very slow rate. He also has the financial means to both adjust his life and support research in the field.

The energy he has put into this fight so far has had significant gains. Winthrop has pitted his knowledge of Washington politics and previous success in the non-profit sector to fight for those who share his diagnosis. He has worked with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to create an ALS Registry. This effort has gathered information via questionnaires from 15,000 patients so far. Winthrop also works with the CDC as a member on an advisory board to evaluate clinical trials and publish legitimate tests online. In this way, Winthrop hopes to “separate quackery from really good, bonafide research” as more quality data is gathered and shared within the community.

As beneficial as the registry is, the $10 million price tag needs congressional funding every year, one of five legislative projects Winthrop is currently backing. The potential fruits are more than worth the fight. To him, the registry is “the best thing that we have. It’s not perfect, but it’s the best thing we have to connect people with ALS in one place.”

Winthrop also counts the Federal Food and Drug Administration as another partner in cutting through the lack of information for and about the ALS population. He serves as a co-chair of a committee currently working on an FDA Guidance, what he calls a “bible for ALS.” As the FDA realized their limits in terms of taking on this project internally, the ALS Association was tapped to spearhead the effort. The Association in turn reached out to 19 different organizations, academics, researchers, and pharmaceutical representatives to produce the document.

By expanding the amount of participants, Winthrop said the Guidance hopes to “encourage more pharmaceutical companies to enter the field of ALS research and give them tips on how to streamline the application and testing process, which we hope will accelerate the move towards an effective treatment or cure.”

Navigating the practical, day-to-day experience of ALS patients is another area that takes much of Winthrop’s energy. The danger of falling is dire for someone with ALS, according to Winthrop. In his view, patients are only one or two falls away from a steep decline in their health.

Winthrop speaks from experience. In June of 2016, he stepped off a bus in New York City. While his legs and feet did their part, his arms simply could not do the job of catching him before he went down in the street, face first.

“If I fall, I go down like a tree,” said Winthrop. A fractured jaw, three cracked teeth, and broken bones in his left hand served as a “wake-up moment” for him. As bad as the fall was, he was lucky enough to avoid irreparable damage to his vision and brain. Since then, avoiding any these dangers in his home has become a top priority to him.

Thanks to his involvement with the Boston-based non-profit Institute for Human-Centered Design, Winthrop said that he is “convinced that this house is going to add years to my life.”

“Fall prevention was one of the absolutely central features to this house that the architect just pounded into us over and over and over again,” said Winthrop. Natural light is key, and every entry way in the home boasts a seamless floor, making for easy passage by foot or wheelchair. By adding features through a PEAC system made by Promixis, Winthrop can answer the door, adjust lights, and open and close windows through his phone. Automatic doors use motion-sensing to give him open access everywhere. In this way, every avenue of daily living remains open to him.

“The house is almost like a caregiver for me,” Winthrop said. “It makes it possible for me to move around in my own space, without needlessly using energy to open doors.”

More than anything else, Winthrop attributed his continuing efforts to the support of the people around him. This piece of his situation is more than a critical component for him. Winthrop said he has personally observed entire families “left in shambles because of one person getting the disease.” He shared that stories have come to him of couples getting second mortgages, liquidating retirement funds, and pulling at every conceivable asset until the surviving partner is left alone without any means of income.

Winthrop said that while he has no statistics on the topic, he draws a sense of high divorce rates among patients as well.

“Nobody really wants to explore that too deeply,” said Winthrop, “but I totally get it. Not because my own marriage is on shaky ground, thank god it’s not. But I heard one story about a woman who left her husband at a retirement home with a note saying, ‘I love him too much to be able to continue to try to care of him.’ Basically she was wrung out and spent and gone, and it was just like leaving a baby in a basket at an orphanage.”

At its heart, ALS is what Winthrop calls “a horrifically isolating disease for most people who get it.” For him, the loss of connection that comes with the slow dismissal of the ability to speak, be mobile, and even type on a keyboard cannot be topped.

“Now what’s more isolating than that?” he asked.

The Art of Healthcare

An extraordinary effort to bridge these losses can be found at the ALS Clinic at the UCI Medical Center in Orange, California. As daunting as this terminal, mystifying field can be, Dr. Namita Goyal, director of the clinic, spoke to the opportunity she has found to offer grace in spite of a diagnosis without a cure.

Sevgi Hemservi and her daughter-in-law, Tina, listen to one of the specialists at the ALS Clinic at the UCI Medical Center. (Photo by Loud Owl)

Once patients arrive, outside professionals have ruled out other diseases and referred them to the clinic. Goyal said patients have described horrific scenes in which a doctor will tell them they have this disease, then send them home to make arrangements and prepare to die in two to five years.

Goyal shared how she does everything she can to be gentle and considerate in delivering news of this kind.

“There’s a real art to giving someone the diagnosis,” said Goyal. “I’d like to think I try my best at it. I’ve had patients tell me that there’s no one else they would have wanted to hear it from.”

On days designated for this specific kind of care at the clinic, Goyal and her team start in the morning, around 10. Between five to 10 ALS patients are seen on these days, and the team aspect of the clinic’s technique is an important one. This approach diverges from how patients often need to make several stops to different offices to see the specialists they need. By bringing social workers, physical, speech, and respiratory therapists all under one roof, as well as representatives from the Orange County chapters of the Muscular Dystrophy Association and the ALS Association (both of which help fund the clinic on a regional basis), a two-hour visit takes a comprehensive accounting of each facet of a patient’s health.

This approach of bringing multiple disciplines under one roof has shown positive results in the lives of patients with access to clinics like Goyal’s. According to the non-profit ALS Worldwide, these multi-disciplinary clinics have worked to improve quality of life and decrease depression for patients, as seen in studies conducted in the Netherlands, where doctors have honed these techniques for over a decade.

“It’s really nice to just go to one place,” said Christina Schwartz. Her and her husband have been coming to the UCI Medical Center since January 2013, shortly after her diagnosis in 2012. “The appointments are long, but it’s worth it,” Schwartz said.

On exam days, a cross section of the profoundly personal and clinical can be found in each room at the clinic. The professionals on staff balance candidness and compassion as they meet with each patient and their family members. Nothing is rushed, and no question goes unanswered, as dire as they can be at times. The enormity of each situation brings not a few tears among the patients and their people, including Sevgi Hemservi.

Hemservi arrives in a wheelchair with her daughter-in-law, Tina. Even at 80 years old, Hemservi’s age all but vanishes under the strength she brings to the appointment. Concerns about her own disabled daughter pepper the questions she is asked by each specialist, as well as a distinct distemper with the loss of abilities to help and live how she wants.

Hemservi laughs as Tina and staff look on. (Photo by Loud Owl)

Physical Therapist Patrick Tierney gently tests her flexibility by turning her limbs in his hands. He tells Hemservi how stretching multiple times a day can help combat contractions in her tendons. Aside from muscular work, Tierney also recommended a Trilogy breathing device, a non-invasive, mask-like apparatus that works to strengthen the diaphragm.

Surprisingly, amid all of the updates and check-ins that come from one specialist after another, Hemservi is given to bouts of laughter. An inability to control emotions is a common side effect of ALS, and her mirth is certainly catching. Tina cannot help but laugh along with her mother-in-law at these times. She hides her smiles as best she can, attempting, with mixed results, to discourage Hemservi from laughing even more as the doctors work.

Like any fit of deep-rooted laughter, tears emerge in the corners of Hemservi’s eyes. Then, as quickly as outright glee arrived on her face, these tears draw Hemservi’s features downward. Her smile is lost as belly laughs turn to sobs while Goyal looks on.

“I can’t control it,” Hemservi says. These four words can define almost everything in the room. Her body. ALS. The arbitrary fluctuations that throw her from bliss to despair with hardly a moment between them.

“This is not fair,” Goyal says as Hemservi weeps.

The transition back to collecting herself is just as unanticipated as the others. Hemservi nods, then meets Goyal’s eyes again. Patient and doctor do not skip a beat, and they talk about Hemservi’s last visit in January on 2017, during which Hemservi’s breathing ability logged in at 80% capacity. The month of May sees her at 48%, speaking to a rapid deterioration of the body’s abilities.

With Hemservi’s next visit scheduled for July. Goyal shared that the time to utilize a feeding tube might come too late. On the equipment front, Tierney shared how a neck brace can lead to aspiration, when fluids or other foreign substances drop into the lungs as the neck straightens. But the need to address neck muscles weakened by the disease leaves them in a “catch-22,” according to Tierney. He shared how family members would be the best source for movement when needed, as adapter pieces designed for her wheelchair would not be able to keep up with the progress of the disease.

Unimpressed, Hemservi does not flinch with this news.

“I don’t want to live too long,” says Hemservi. She then repeats concerns about her disabled daughter, such as when a new wheelchair for her will get to the house, as well as a customized armrest to keep her comfortable. Regardless of her current state, the mother in Hemservi stands as an indomitable caretaker.

After seeing to her physical condition, professionals enter the room to assist with insurance and the rising cost of care. Natalie Villegas from the Orange County Chapter of the ALS Association shares information with Hemservi and Tina, telling them to reach out any time for help.

Issues with money plague patients across the board, since caregiving services are not covered by medical insurance. Caregiver fees kick into overtime after nine hours per day or 45 hours per week, which lead to an exponential growth in bills that can reach into the range of $100,000 to $120,000 per year.

Financial burdens can be crippling to patients and family members alike. Barbara Newhouse, president and CEO of the ALS Association, said that the current state of medical care might not benefit so much from overhauls as consistency. Newhouse said that two individuals can call Medicare “on the same day, and get two different answers for the same situation.”

While organizations like the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs offer clear and prompt benefits to people within their purview who have ALS (due to veterans from various conflicts being up to twice as likely to contract ALS than civilians, according to a study by the Institute of Medicine, among others), Newhouse strives for a day when the same aid will be available to all patients.

“What I would like to see, in terms of assistance for people with ALS, is that we would be able to get past having haves and have-nots,” Newhouse said, “and be able to have a system where all the people with the same disease could get good benefits.”

A significant step in ensuring the ability to communicate for all ALS patients will be taking a major political step in the near future. The Gleason Act, signed into law in July 2015 through the efforts of former professional football player Steve Gleason, covers the cost of speech-generating devices under Medicare. Though it currently remains in effect in the United States, the law is not permanent. The new Steve Gleason Enduring Voices Act (H.R.2465) introduced by Representative Cathy Rodgers of Washington in May of 2017, seeks to put a permanent status on funding communication devices forAmericans living with ALS. Upon its introduction, the law was quickly passed to the Subcommittee on Health, after which it will soon be voted on by the House of Representatives.

In the mean time, continued communication and other practical concerns plague Hemservi and her family. Tina shares how reactions from family members have varied between despairing to systematically clinical. Responses are only exacerbated by unmet or muddled needs, such as an absence of routine support and overlapping caregivers for both mother and daughter.

These issues are all that concern Hemservi. When a social worker brings up the end of life and a new spiritual phase to follow, she made her feelings clear.

“Ashes to ashes,” Hemservi said, without drama or lack of clarity. Without believing in a heaven to come, she still asserts the value she sees in the life she’s led until now.

“I had a good life,” said Hemservi.

Wehbe and Rita Wehbe. (Photo by Loud Owl)

The different timelines, ages, and symptoms that come with each patient deviate widely. Wehbe Wehbe shared that his symptoms began at the end of 2011 with abnormal feelings in his tongue, as well as his right thumb. In the same way that these symptoms diverge from the more common signs doctors look for, the abilities that Wehbe still holds onto after six years stand out.

Though he has lost most of his strength in his arms and hands, Wehbe can walk fine, and even jump off the ground. He demonstrates as much to Goyal and his wife, Rita. His hops are numerous, lifting him off the floor in tandem with the smiles that fill the exam room.

As with other patients at the clinic, the transitions between lightness and despair come so often that they almost overlap. The continued existence of a physical ability is framed by the certainty that it will be lost soon, which in turn leads to gratitude for the time each patient has left to enjoy with their people.

Wehbe shared his own appreciation for the center’s care and staff, but was also blunt about where he stands on the nature of the disease. Without a treatment or cure, he said the visits feel like a waste of time.

But soon after, Wehbe encouraged other people in his position to use a treatment beyond the clinic’s walls. He shared how marijuana, administered by way of candies, lessens his pain, helps him sleep, and bolsters his appetite. After about two years of use, Wehbe had only two words of advice when it comes to other ALS patients using marijuana: “They should!”

Rita’s hands hardly ever leave Wehbe’s for the entirety of their visit. Her support is palpable as Wehbe advised those who share his condition to not let it weigh on them as much as possible.

“Don’t think about it,” said Wehbe, his wife’s arms wound around his own. “Live your life normally.”

Physical Therapist Patrick Tierney tests Dennis Matthis' flexibility. (Photo by Loud Owl)

Deep consideration on the part of both partners is a common element within the clinic. Dennis Matthis has been living with a slowly progressing case of ALS since 2009. After recently finding an increasing difficulty with swallowing, he admitted to Goyal that he did not want to use a feeding tube, since he thought it would make more work for his wife, Eileen, who was in attendance along with his two sons.

After a surprised laugh, Eileen did not hesitate to say she was happy to help in every way she could, and would not mind assisting with the tube at all.

Once all of the specialists have completed their visits with Matthis, his sons turned to him and Eileen. The takeaways from the team included a recommendation to stop chewing food, the insertion of a feeding tube, and a new prescription for the Trilogy ventilator. With so much to take in, the family’s concerns were many. For the two men, so much life-changing news was a lot to take in at once. They voiced their concerns that it might be overwhelming for Matthis and Eileen.

Eileen shook her head. She said that for her, the information came as guidance, and therefore relief, in the midst of so many unknowns. To put definitions and technology to work with her husband, in her eyes, would only help the two of them meet whatever comes next.

Matthis agreed. As a recovering alcoholic, he said that he is used to taking life as a “day at a time.” A lone finger trembles on his knee as he speaks about how, while letting go of so much, he has no hesitation in saying that, “Life is still good.”

Research and Skepticism

With everything the UCI Medical Center does in terms of patient care, the facility serves as a research facility as well.

After the stratospheric success of the Ice Bucket Challenge, Goyal said that UCI drew her from being on staff at the Harvard Medical School’s Massachusetts General Hospital to southern California, since it stands as one of the more active clinical trial sites for ALS.

“I thought, wow, that’s where I can potentially make a difference for someone,” said Goyal.

Five clinical trials are in action at the moment, the most done in the field of ALS by UCI at any one time. The center is also preparing to announce new trials in a different field before the end of the year, which marks 2017 as “a pretty exciting time” for Goyal.

“In every meeting I go to, new genes are identified,” Goyal said. But, with all of the understandable buzz generated by these leads into the cause or causes of ALS, Goyal encouraged skepticism when it comes to any new information.

For example, a study on Italian football players and the prevalence of ALS among them seeded fears that exercise-intensive populations might be at a higher risk for the disease.

With all of the understandable interest that theories like these generate, Goyal said that these claims simply do not have evidence to back them up. “There’s no real hard data that supports that there is potentially an environmental or exercise-rich factor,” she said.

Likewise, anecdotal successes permeate the media. There are claims of progress in battling the disease using certain supplements, for example. Goyal said that “as a researcher in the field, and seeing a large number of patients with ALS, none of us are really convinced yet that we’ve seen any marked improvement.”

When it comes to finding anything in the way of a smoking gun, much work remains to be done, according to Goyal.

“It’s really honestly so complicated still,” said Goyal. “Of all the research meetings that I go to, all of the national and international meetings, I don’t think that anyone’s come very close to identifying one mechanism over another. I’m still pretty skeptical about knowing exactly where this mechanism is coming from.”

However, Neurontin’s gabapentin medication, used to treat epileptic seizures, has showed favorable results. One-third of ALS patients treated with the drug did not show progress in their disease for six months, a result that Goyal called “one of the more remarkable studies that has shown some pretty interesting data.”

As excited as some might be by this development, Goyal urged temperance. “It was a small number, and we have to interpret those results with caution, which is why we are doing the current study [on gabapentin] right now.”

Quality of Life

As ALS robs a person of their physical abilities, seemingly impossible choices move to the forefront of patients’ lives. Monetary demands that come with wheelchairs and communication devices can force people into having to choose between basic needs like mobility or the ability to speak with their loves ones.

Research to help alleviate these dilemmas is taking shape at California State University at Fullerton. Dr. Kiran George, professor in computer engineering at CSUF, is leading his students to assist with all kinds of disabilities, including ALS.

George’s students, however, have an added challenge: their designs must fall under a $200 price point.

Advanced systems used to track eye movement can cost upwards of $12,000. Medical insurance will usually cover about 60-70% of that total. These demands create an immediate need for low-cost products to help with the drastic changes that come with ALS.

The price parameters, according to Bryce O’Bard, a graduate student at CSUF who has been working on one such project, aim at gaining the best for people in need, regardless of who they are or what they can afford.

“It’s really about quality of life,” said O’Bard. “We don’t feel like it should cost people thousands of dollars to access that just because they’re disabled.”

O’Bard’s current project uses electrodes attached around the eyes of a subject to read voltage generated by the muscles at this location. The system then works to “translate those eye movements into controls that can be used to control, for instance, an iPad or iPhone over Bluetooth,” O’Bard said.

Dominic Nega (left) and Bryce O'Bard attached electrodes to James Blount to test electroocularography equipment. (Photo by Loud Owl)

Eye movement is an ideal outlet for ALS patients to communicate through, as the neural network responsible for extraocular muscles tends to last longer than those found in other parts of the body (research into why this is shows promise as well). Electroocularography, or the harnessing of signals given off by these areas, can be used to vault the barriers to communication brought on by ALS.

Dominic Nega, another student from CSUF working with O’Bard, helped test one particular piece of equipment at the home of James Blount. Blount has lived with a form of ALS that keeps him in a wheelchair, but he still has the ability to speak, making him a prime candidate for the test, as he can offer auditory notes when needed.

An iPad is situated in front of Blount before electrodes are placed at the outside edge of each eye, then above and below each socket. The signal transmitted by the muscles, called a potential, travels through the electrodes to a wire, where it enters a micro controller. The controller, working from information levels customized to each user, determines whether the signals it receives are strong enough to act on a given action. Voltage in the range of three volts is read by O’Bard’s and his team’s software, which is calibrated to pick up on these minuscule movements as a subject looks from one direction to the next.

Once a series of test glances are measured by the electrodes, the software is calibrated to respond to the user’s respective muscle movements in a way that is sensitive to their unique signature, but not overly so. Holding the look for too long can strain muscles, and the hardware is sensitive enough to pick up on quick motions. Looking left moves the cursor, a blue box that surrounds different icons on the iPad, to a previous section, right moves forward. Down is like clicking on a command with a mouse.

O'Bard and Nega adjust their software to pick up on Blount's feedback. (Photo by Loud Owl)

O’Bard and his team observe Blount’s performance as he is asked to take on different tasks to the best of his abilities. As a proof-of-concept trial, their goal is to gather information from ALS patients who are willing to try the technology.

After the tests are finished, O’Bard shared that honest opinions from users provide some of the best guidance for the future of the device. When asked, Blount said long looks in one direction misled the software when his intentions were different. He also shared that he did not think people would want to have electrodes attached to their faces.

To wear the electrodes is certainly noticeable. More advanced systems, using devices like the cameras made for Apple computers, for example, read the pupillary reflex, or the dilating or shrinking of the eye’s pupil. However, Apple does not allow access to their software or hardware for projects like the one O’Bard is working on currently. Therefore, he and his team opted for electroocularography, and might choose something along the lines of a set of glasses to replace the electrodes as they move forward.

O’Bard listened to all of the notes Blount shared, and took care to tally them for future incarnations of the device.

“Does it work? Yes,” said O’Bard. “Can it be better? Of course.”

Once data is collected from each user, the product can “be improved on from there just by using time and man-power,” O’Bard said. “You don’t have to throw more cost into the hardware.”

At the end of the day, the test with Blount gave the students what they came to find.

Blount, Nega, and O'Bard discuss the test. (Photo by Loud Owl)

“We got proven functionality, like we were hoping,” O’Bard said. The system is not “super-intuitive,” he said, which had been confirmed by other users. But Blount’s patience and willingness to engage were valuable.

The additional variables that ALS presents bring other challenges as well, especially where symptoms can vary from person to person. “ALS is a tricky one especially, since everyone is so different,” said O’Bard. “For instance, [Blount]’s able to move his neck still, and there are a lot of patients where that is the first thing to go.”

In the end, any completed test is a good test in O’Bard’s eyes.

“His enthusiasm and willingness to learn were really good,” he said about Blount, “which helped a lot.” Blount was also able to choose letters and options faster as time went on, leading O’Bard to conclude that, “overall it went well. The test went well, and he was a good sport about it.”

Living in the Present Moment

When asked about the source of positivity that runs through many ALS patients, most are quick to name family, community, and non-profits. They are all fine answers. No shortage of energy can be found among the people working to fight for those living with this disease. But, as ALS diminishes the ability to connect with these sources of help, a few patients spoke to the strength they find from within, and how a spiritual approach has fostered its growth.

“It is a daily challenge to figure out a way not to get swallowed up by the disease and everything that it brings with it,” Winthrop said. With this pervasive presence in his life, Winthrop said he has found different ways to put mindfulness into practice, however and whenever he can.

“Sometimes it’s sitting in a dark room,” said Winthrop. “Sometimes it’s out walking my dog. Sometimes it’s sitting around watching “Modern Family” with my family, and really, really being able to fall fully into the present moment, and kind of let ALS fade into the background, for at least periods of time.”

Winthrop said that awareness of the disease also magnifies certain experiences that he knows will not be around as long as he wants. For example, he shared that recent changes in his body have indicated that the time he has left to eat normally may expire sooner than later.

“That really heightens your awareness of the meal you have in front of you today,” said Winthrop, “when you realize that you may not be enjoying a meal like this a year from now.”

When faced with more and more things one has to let go of, anger, sadness, and even despair can crawl into the mind, according to Winthrop.

“Anybody with ALS spends a certain amount of time feeling sorry for themselves,” Winthrop said. “Can’t help it. It’s a crappy disease, it’s a crappy set of circumstances. So I’m not going to say that I never feel sorry for myself.”

Winthrop has seen these emotions at play in plenty of other patients as well. He is also forthright in saying how these mental states are more than fair to feel. Many patients express fear, impatience, and feeling like they are not being heard by professionals in the field, or the world at large. A terminal disease draws edges out of these emotions that can be searing, which Winthrop understands well.

“The anger is justified,” said Winthrop. “I’m not going to tell people, ‘Hey, hey, calm down.’”

At the same time, Winthrop said that he cannot tolerate when this anger is fired in inappropriate directions.

“I’ve seen doctors and nurses drawn and quartered by people in the ALS community,” Winthrop said. “Just scathing, damning diatribes, and I don’t think they deserve a bit of it. These are people who are devoting their lives to trying to find an answer to this complex knot of riddles. But, I feel that I recognize that anger is a very real part, and will always be a very real part, not just anger, but these other words I’ve used, like alienation and distrust. It’s part of the stew.”

The mixtures churning about in Winthrop himself draw an especially poignant meaning when it comes to his own case. Since his disease is progressing relatively slowly, his vantage point earned him a warning from another slow-progressor.

“‘If you do have a slow progression, look out,’” Winthrop was told by another patient. “‘Because you’re going to see friends wither and die right before you. And then you’ll make new friends. And you’ll see them wither and die, too.’”

The words inhumane and heartbreaking come up when Winthrop described watching the disease run its course in others. Any answer, much less comfort, might seem impossible under such circumstances. However, when faced with these realities, a pragmatic approach is never far from Winthrop’s mind.

“When I find I’m falling too deep into that hole,” said Winthrop, “I say, ‘Well, what do I have control over? What can I do that might make a difference?’” he said. The choices that bloom out of these seeds, according to Winthrop, have played a large role in why he participates in clinical trials, works to advance research, and disperses as much knowledge as possible to the public.

As hopeful as he is, Winthrop is practical when it comes to the mammoth undertaking of trying to understand and cure ALS.

“There’s no way we’re going to beat this disease,” Winthrop said of his own case, “which is just stating the obvious. But there is no way this disease is going to end without a cure or an effective treatment, and the only way we’re going to get a cure or treatment is through clinical trials. So, dammit, I’m going to do the best I can, and get in as many trials as I can.”

The mind can reel at the prospect of this diagnosis, much less reasons to push through it. Former business owner and Orange County resident Kevin Allen spoke to how his own faith has formed a wellspring in the midst of having an “incurable, terminal disease with a 2-5 year life expectancy. It is like having a guillotine hanging over your head and not knowing when it will drop!”

A talented singer and former host of a radio program within the Orthodox Christian community, Allen’s first symptoms showed by way of a slurring and raspiness seeping into his voice. After undergoing a procedure to “plump up” his vocal cords using a material akin to Botox, Allen looked for more answers. It was then that a neurologist diagnosed him with Bulbar Onset ALS.

Even though no provably effective treatment exists at the moment, Allen said that pursuing amniotic stem cell therapy has yielded observable results for him. Though taking care to say that FDA trials have not shown that stem cells can slow or cure ALS, his subjective experience tells him that “something is working physically in slowing the onset.”

The psychological edge that has come with this development, according to Allen, “offers me hope that something may help slow the progression or rate of the disease.”

As encouraging as these results might be for him, the reality that comes with his diagnosis is something Allen refuses to ignore.

“Without hope and faith, I knew that a diagnosis like this one, with no cure or treatment except palliative care, could turn quickly into despondency,” said Allen. “I did not want to travel to the world of depression and despair. So I decided at the outset that I would trust in God and not lose hope and faith. This was an act of will.”

As staunch as his will is, Allen said it is not unmarked by low points. “I must admit that when I feel weak and unwell, I am often challenged by depressing thoughts,” Allen said. “At times my mind scurries to thoughts of the future and what might happen. But I try to live in ‘the present moment,’ as that is reality.”

The solace of living in the present, for Allen, is bolstered in no small part by his faith. As he tells it, a healthy dose of humility helps him to take each moment in stride as well.

“Being honest, I am no saint,” Allen said, “so I cannot say that I have had an epiphany of ways God’s strength has revealed itself to me, other than that I know God exists, and he is with me. That is my greatest comfort going on this new journey.”

The faith that each patient puts into the people around them, from professionals to family members, can carry a double edge for some. Blythe shared how the dynamics have changed between her and her two children, both in her role as a mother, as well as the seeds of empathy that the disease has fostered in them.

“I have to admit that because of ALS, I am not the mother that I wanted to be,” Blythe said. “I can no longer get on the floor to play with my beautiful children. Or even help them when they hurt. ALS has completely stolen this from me, and every day I have to force myself to not be angry and bitter.”

As young as they are, Blythe’s children are often curious about the changes they see in their mother. Her son, now five, will ask why her hands cannot work the way they used to, and why she has to stay in a wheelchair. When these questions come up, Blythe is open about what ALS is and what it is doing.

“I am honest and tell them that I have a sickness that makes my hands and legs not work as well as theirs.”

Her daughter, who has never known Blythe to be any different, does not understand the answers as well when they come. But Blythe has noticed that her condition has brought out something else in her children, which she could not be more proud of.

“Because they are always watching their father taking care of me, my kids have begun to care for others in the same way,” said Blythe. This includes everything from “bringing water to a coughing momma, or making sure that the floor is clear so I can roll on through the room. My toddlers ask if I'm too warm or too cold. All of this shows me how amazing these two little people are growing up to be.”

Choosing to celebrate the places in which she can encourage her children, for Blythe, strengthens her resolve to be a positive presence.

“I may not be able to participate in a lot of activities, but I am still able to read to them, cuddle, and be with them every day,” said Blythe. This cycle of care returns to her through her children, and the nourishment they all receive rises above anything else for Blythe.

“Most of all, I am able to share my immense love with them,” Blythe said. “To see this love, reflected in their eyes, keeps me fighting.”

Special thanks to Kristin Schlick, Eryn and Chad Blythe and their family, Stephen Winthrop, Kevin Allen and his family, Sevgi Hemservi, Christina Schwartz, Wehbe and Rita Wehbe, Dennis and Eileen Matthis and their family, Dr. Namita Goyal and everyone at the UCI Medical Center, James Blount and his family, Dr. Kiran George, Chi-Chung Keung, Bryce O’Bard, Dominic Nega, and everyone at CSUF, Barbara Newhouse and everyone at the ALS Association.